Urgent reforms needed to address heating impaired children's educational needs in India

A growing educational catastrophe threatens India's deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) students. According to a 2014 government poll, more than 19% of these pupils were not in school, highlighting the institutional impediments that impede their entitlement to an education.

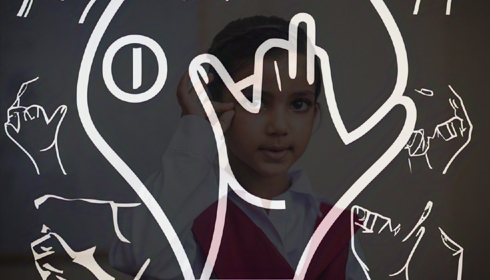

A new study calls on the Indian government to take decisive action by formally recognising Indian Sign Language (ISL), abandoning obsolete oralism practices, and expanding the number of specialised educational institutions for DHH pupils.

Dr Abhimanyu Sharma of Cambridge's Faculty of Modern & Mediaeval Languages & Linguistics, who wrote the study published in Language Policy, warns of the serious repercussions of inaction.

"Thousands of deaf and hard-of-hearing children in India are missing out on school. This has a significant impact on their well-being and future opportunities," he says.

One of the key causes of DHH students' worrisome dropout rate is a lack of access to education in sign language. Despite overwhelming evidence that oralism is unsuccessful, many Indian schools continue to promote it.

"Outside of India, oralism is widely criticised, but the majority of schools in India continue to use it," Sharma says. "Gesturing isn't sign language. Sign language is a language in its own right, and these youngsters require it, he adds.

Systemic Neglect: A Crisis of Numbers

According to Dr Sharma's research, ISL remains stigmatised in the majority of Indian schools, preventing DHH pupils from receiving a proper education. The lack of ISL recognition causes thousands of students to struggle to grasp classes, resulting in low academic performance and significant dropout rates. He draws on personal experiences, including a deaf classmate in Patna who was unable to acquire a proper education due to a lack of sign language teaching.

Although the Indian government has made some excellent efforts, such as creating the Indian Sign Language Research and Training Centre in 2015, the scope of the problem requires far more. There are currently just 387 schools for deaf and hard-of-hearing students across the country, which is insufficient considering the DHH population.

Official figures have also grossly understated the number of deaf and hard-of-hearing people in India. The 2011 census indicated approximately 5 million DHH individuals; however,, the National Association of the Deaf projected this amount to be closer to 18 million in 2016. These disparities impede the development of effective policies and the distribution of needed resources.

Call for Policy Overhaul

Dr Sharma's report offers a strong case for quick reforms. A critical step towards inclusiveness is the constitutional recognition of Indian Sign Language (ISL) as an official language. Such a move would secure government funding and policy backing for its widespread implementation. Without this acknowledgement, ISL continues to exist in a policy vacuum, limiting its reach to the kids who require it the most.

Equally important is the expansion of special schools for DHH pupils. With only 387 universities in India, the number falls well short of addressing the needs of the current student population. To close the gap and ensure that no child falls behind owing to a lack of educational infrastructure, the government must open significantly more schools.

However, primary education is just one aspect of the larger picture. Due to a shortage of further education opportunities, DHH students' academic advancement is frequently impeded. Institutions like the St. Louis Institute for the Deaf and Blind in Chennai are rare examples of committed support, but India requires many more such institutions and universities to serve this community. Without access to higher education, DHH residents' job prospects remain low.

Sign language interpreting training is also an important part of inclusive education. Without enough interpreters, the potential benefits of ISL recognition and school growth will go unfulfilled. Universities must implement and expand interpreter training programmes to establish a strong support structure for DHH students.

To ensure the effectiveness of these measures, governments must conduct regular policy impact evaluations. Tracking and measuring reform outcomes will assist in identifying gaps and improving methods, ensuring that policies have a genuine impact on DHH education rather than serving as simple token measures.

Beyond legislation and infrastructure, public awareness initiatives are critical for combating social biases against deafness and sign language. Negative social views continue to isolate DHH people, making it difficult for them to integrate in educational institutions and the labour force. Public outreach programs can help normalise sign language and increase acceptance among the DHH community.

Finally, the Indian government should engage in research and funding to help develop targeted teaching methods for DHH kids. Research-based approaches will result in better learning experiences, improved outcomes, and more successful policy implementation.

Legislative Gaps and Implementation Failures

Despite legislative measures like the 1995 Persons with Disabilities Act and the 2016 Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, major inequalities remain. While the former removes the necessity for DHH students to acquire three languages, it does not acknowledge ISL or offer a structured substitute. The latter requires teacher training in sign language, but its execution is grossly inadequate due to a severe dearth of trained teachers.

The reduction in parliamentary discourse around DHH education until the 2010s reflects previous neglect. However, with a recent rise in legislative attention, there is still potential for genuine change—as long as fast action is made.

Time for the government to listen.

The Indian government is at a critical moment. Failure to accommodate DHH kids in mainstream education not only denies them opportunity but also violates India's constitutional commitment to inclusive education. While previous efforts were well-intended, their effectiveness has been restricted due to poor execution and insufficient funding. Recognising ISL as an official language is no longer a choice; it is an urgent need.

The world is moving towards inclusive education policies, and India cannot afford to fall behind. Millions of DHH individuals and families want to be heard. The government must act immediately, before another generation falls behind.